The Anointing of the Sick is most commonly associated with the Roman Catholic Church and, as such, this article explores the rite from the Catholic faith’s perspective. In Catholicism, the Anointing of the Sick is considered a sacrament and centers on the Lord’s healing presence and the forgiveness of sins.

Crosswalk.com Contributing Writer Updated Aug 05, 2024

The Anointing of the Sick is a biblically-based ceremony performed in certain Christian denominations for the benefit of a person who is ill, frail from age, or about to have major surgery. The ceremony petitions God for the person’s spiritual and physical healing through the Holy Spirit, and is meant to unite the person with the suffering of Christ.

The Anointing of the Sick is most commonly associated with the Roman Catholic Church and, as such, this article explores the rite from the Catholic faith’s perspective. In Catholicism, the Anointing of the Sick is considered a sacrament and centers on the Lord’s healing presence and the forgiveness of sins.

Most anointings in the Bible consisted of the smearing of olive oil or ointments on a person or object for secular or sacred purposes. Anointings with olive oil were commonplace in Biblical times, and having enough olive oil to use for anointings was a sign of prosperity and blessings (2 Kings 20:13 ESV; Joel 2:19). Scripture also notes that some anointings occurred spiritually through the infusion of the Holy Spirit.

1. Commonplace anointings with oil: In Biblical times, it was traditional to anoint people or objects for secular reasons. For example, Jews showed hospitality to their visitors by anointing the visitor’s head with oil (Luke 7:46; Psalm 23:5). Further, Jews anointed their own head and bodies with oil to smooth and refresh their hair and skin (Ruth 3:3; Psalms 104:15). In addition, the Bible tells us that in times of war, soldiers prepared their shields by smearing oil on the shield’s leather to make the leather less susceptible to cracking and, thus, make the shield better-suited for battle (Isaiah 21:5).

2. Medicinal anointings with oil: Oil was also used for medicinal purposes to heal the sick and soothe the wounds of the injured. For example, the prophet Isaiah mentions olive oil’s therapeutic qualities in his writings (Isaiah 1:6), and the Good Samaritan knew to mix oil with wine to dress the wounds of the man who fell among robbers (Luke 10:34). Further, St. James also recommends anointing the sick with oil to help them recover from their infirmity and to confer upon them the forgiveness of sins (James 5:14-15). The Bible also records that the Twelve Apostles healed many of the sick in their day by anointing them with oil (Mark 6:13).

3. Religious anointings with oil: The practice of anointing with oil for religious reasons was also customary in Biblical times. To “anoint” in a theological context means to smear or pour oil over a person or object to set it apart for divine use. Prophets, priests, and kings were anointed with oil to symbolize their divine appointment to God’s service (1 Kings 19:16; Exodus 29:21; 1 Samuel 16:13). Fragrant ointments were also used in religious rituals to anoint the dead to prepare them for burial (Mark 14:8; John 19:39-40).

In a similar way, objects were also consecrated with oil to be set apart for religious use. Scripture tells us that objects anointed with oil included: the Ark of the Covenant, the Tabernacle, altars, lampstands, and pillars (Exodus 30:25-29; Genesis 28:18).

4. Religious anointings with the Holy Spirit: Scripture also declares that people can be anointed with the Holy Ghost. The most prominent example of this is, of course, Jesus, who was anointed with the Holy Spirit and power (John 1:32-42; Acts 10:38).

Aside from Jesus’s anointing with the Holy Spirit, Christians are anointed by God with the Holy Spirit who dwells in us (1 John 2:20; 2 Corinthians 1:21-22). A Christian’s anointing with the Holy Ghost differs from Jesus’s anointing in that God imbued Jesus with the Holy Ghost without limit so that all the fullness of deity dwells in Jesus Christ (John 3:34; Colossians 2:9).

The Roman Catholic Church considers the Anointing of the Sick—formerly known as Extreme Unction—to be a sacrament. A sacrament is a ritual performed to convey God’s grace to the recipient through the power of the Holy Spirit.

The practice of the Anointing of the Sick is based primarily on James 5:14-15, which states:

Is anyone among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer of faith will save the one who is sick, and the Lord will raise him up. And if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven.

The sacrament of Anointing is also grounded in the Twelve Apostles’ practice of healing the sick with anointing oil (Mark 6:13).

God promises to heal His faithful and the sick are anointed because they are petitioning God for this healing, if it’s in His will (Exodus 15:26).

Scripture gives examples of God working through ordinary people to heal the sick through the ordinary person’s anointing them with oil, laying hands on them, and praying for them (James 5:14-15; Mark 6:13). Today, Catholics request the sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick to ask God for a similar healing. The person requesting the anointing must be either gravely ill, frail from advanced age, or facing major surgery (Catechism of the Catholic Church “CCC” 1514-1515).

Catholics believe that during the Anointing of the Sick, Jesus Himself—through the rituals of the priest—touches the sick or frail person to spiritually heal them from sin and, if it’s in God’s will, also from their physical (or psychological) ailment (CCC 1504, 1512). Catholics believe that even where there is no physical healing, the main purpose of the anointing is to heal the recipient spiritually through the Holy Spirit’s gifts of strength, peace, and courage to endure the pain that accompanies the sick person’s ailment (CCC 1520).

The Anointing of the Sick can be celebrated in the family home with relatives present, in a hospital with relatives or hospital staff present, or in a church, whether only the ill person is in attendance or a group of ill people and their families. The presence of others, although not necessary, helps to assure the infirm person that the faith community that is Jesus’s body is present in prayer.

The Anointing of the Sick ceremony generally consists of the following stages:

1. The sprinkling of holy water on the sacrament’s recipient and others present

2. Introductory prayers during which a priest may include a brief penitential rite if the person to be anointed hasn’t already received the Sacrament of Reconciliation (commonly referred to as confession) prior to the anointing (John 20:19-23)

3. Readings from Holy Scripture

4. The laying on of hands by the priest in anointing the sick person’s forehead and hands with holy oil to petition the Holy Spirit’s presence upon the sick person (Mark 6:13; CCC 1513). During the anointing, the priest says the following prayer:

Through this holy anointing may the Lord in His love and mercy help you with the grace of the Holy Spirit. May the Lord who frees you from sin save you and raise you up (James 5:14-15; CCC 1513).

5. The communal recitation of the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9-13)

6. Holy Communion if the infirm person is able to receive the Eucharist (John 6:54)

7. The dismissal, which includes a blessing

Notably, if the sick person who received the anointing recovers and, at a later time, falls gravely ill again, he can receive this sacrament again (CCC 1515).

The Anointing of the Sick differs from Last Rites in that a person doesn’t have to be dying to be given the sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick. However, when the Anointing of the Sick is administered to someone who is at the point of death, Last Rites may be given in conjunction with the anointing.

Last Rites encompass the administration to a dying person of the Anointing of the Sick, Penance, and Holy Communion. Last Rites focus in particular on the dying person’s final reception of the Holy Eucharist. This is because, just as Holy Communion nourishes the recipient during his journey through his earthly life, Holy Communion also prepares the recipient for his journey passing over into his eternal life.

For this reason, Holy Communion that is given to someone at the brink of death is called Viaticum, which means “provision for a journey” in Latin.

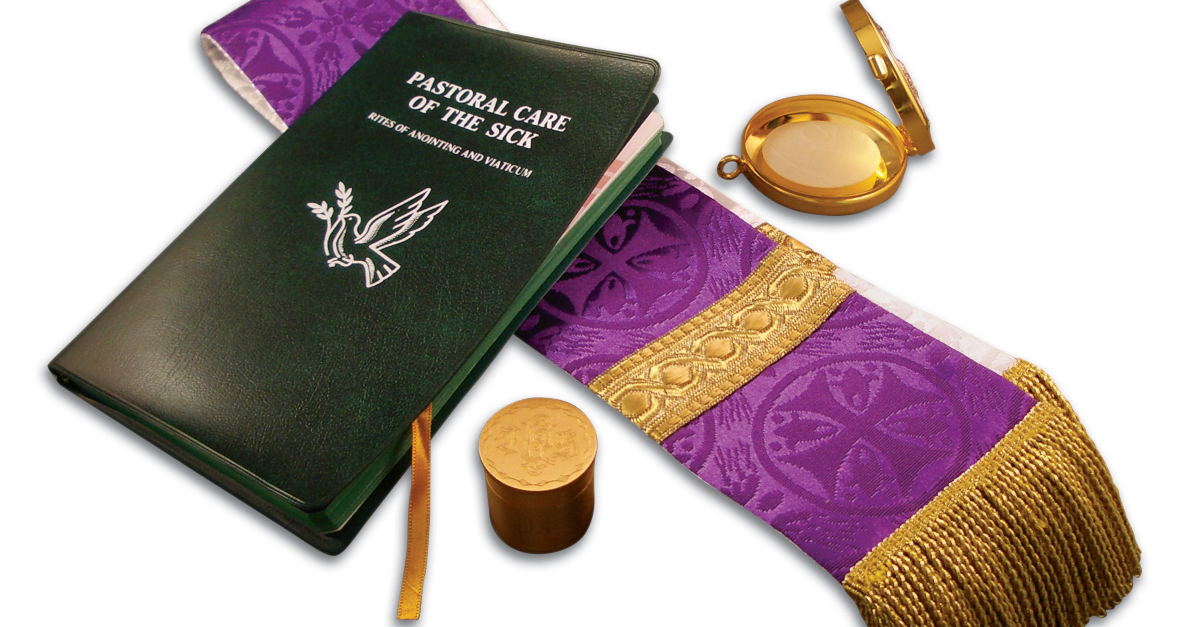

Photo Credit: ©GettyImages Pablo K

The Eastern Orthodox and Anglican churches also consider the Anointing of the Sick to be a sacrament. Other Christian denominations—such as the Lutheran and Methodist churches—don’t consider anointing the sick to be a sacrament but do offer anointing ceremonies, the nature of which varies from church to church.

In recent years, healing services that anoint with oil have become more common in Protestant denominations generally.

The Anointing of the Sick is grounded in the words of St. James to anoint the sick with oil to bring about healing and forgiveness (James 5:14-15). The rite is meant to unite the recipient with the suffering of Christ by calling upon the Holy Spirit to imbue the sick and frail with the strength, peace, and courage to endure the sufferings of illness or old age in Jesus’ name.

Importantly, the sacrament acknowledges that God’s plan for us may or may not include healing us from our physical infirmities. As such, the Anointing of the Sick is not meant to take the place of seeking treatment through medical professionals. Rather, the ceremony adds to the healing resources available by offering the sick person spiritual healing as he or she is prayed over, anointed with holy oil, united with the Lord’s healing presence, and forgiven for prior sins.

Photo Credit: ©GettyImages/yelo34

Dolores Smyth is a nationally published faith and parenting writer. She draws inspiration for her writing from everyday life. Connect with her over Twitter @byDoloresSmyth.