“Soliciting’s not allowed in this neighborhood, so I’m gonna need you to get off my property and get out of this neighborhood before I call the police,” John said gruffly, bursting through his door before I even had the chance to knock.

“I’m not selling anything sir; this is canvassing, and it’s regarded as political speech,” I responded, though I knew right away that the best I could hope for from this interaction was the chance to move on and talk with someone at the next house on my list.

“No!” he snapped. “Any time you’re going door-to-door and talking to people, it’s soliciting and it’s not allowed here. Now get out of this neighborhood — it’s a left at the end of the street, and I’m gonna watch you walk out.”

“All right, have a nice day,” I murmured and turned around. As I walked away, I could hear John a couple yards behind me. He paused at the end of his driveway as I moved faster and wiped the cold sweat off my palms. The next house on my list was midway down the block, but I swiveled around to see John, hands on hips, still standing there, making sure I left the neighborhood. I gave him a little wave (trying my best to seem nonchalant) and turned left.

I took my first breath in what felt like hours, sipped some water, and tried to calm my pounding heart. There were about 50 more houses in the neighborhood I was supposed to canvass, so I looked up another address, took a deep breath, and walked on.

This scene occurred last summer, when I was an intern on a congressional campaign in Washington state that many pundits have identified as one of the closest races of the season, and one essential for Democrats to win to retake control of the House of Representatives. Three candidates vied for the party’s nomination, making it a contentious primary race to the finish line. Before Washington’s Aug. 7 primary, our campaign had a goal of speaking personally to 70,000 people through in-person canvassing; by the day of the primary, we had actually knocked on more than 80,000 doors. While we didn’t talk to someone at every door, our eventual margin of victory probably depended on the face-to-face contacts our canvassers made before the primary. Canvassing is essential in political campaigns. Our result shows it, and the results of countless studies reinforce it.

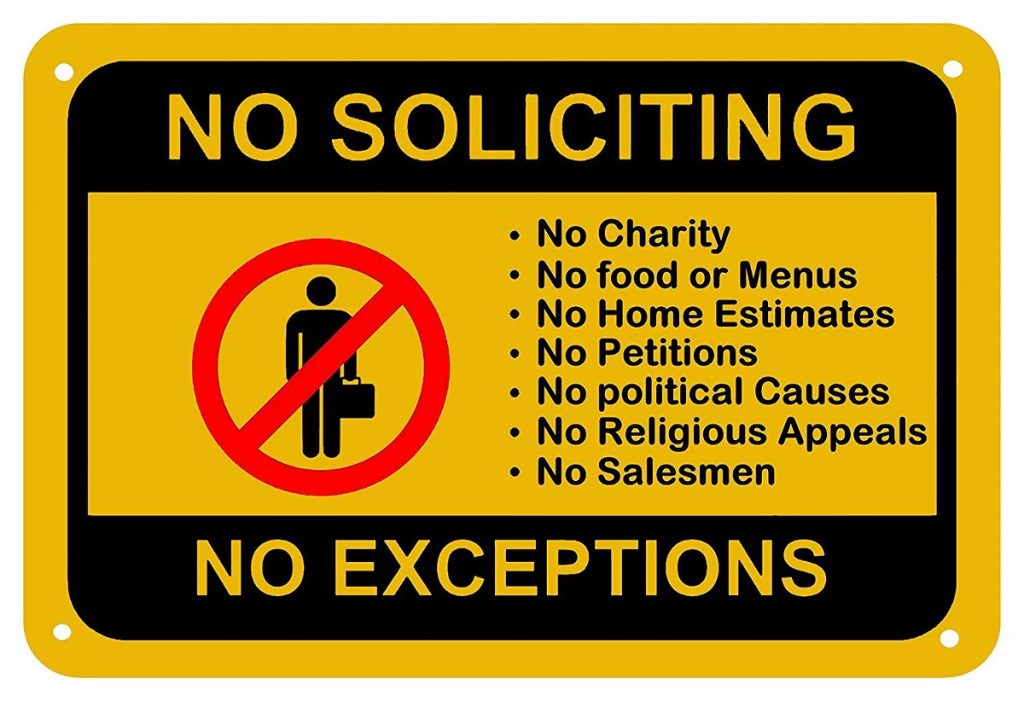

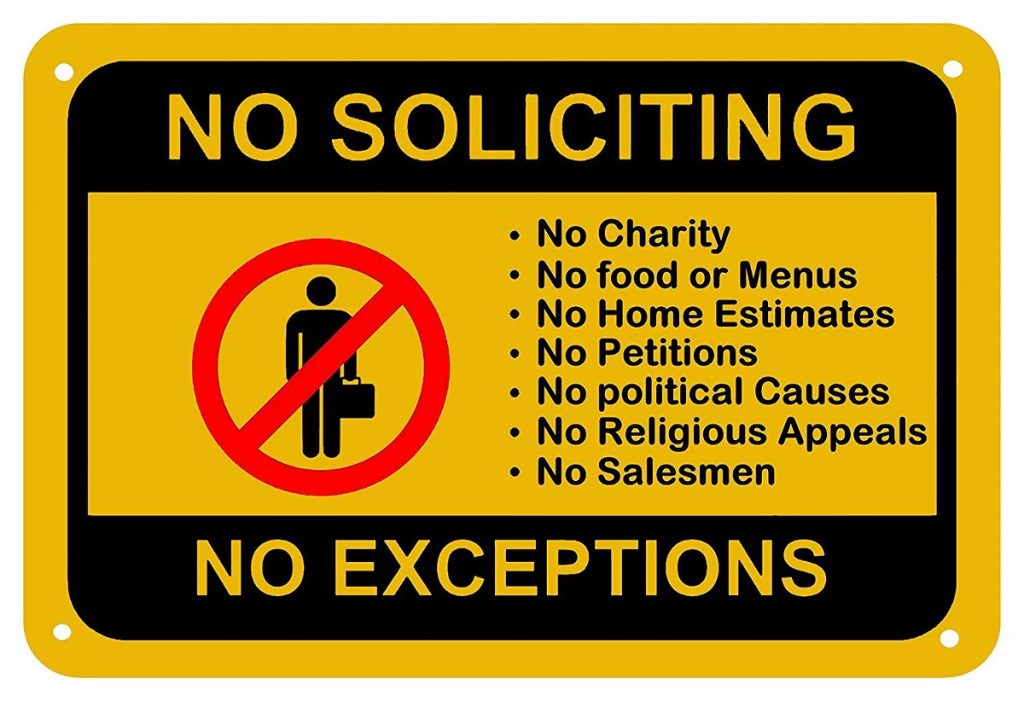

But as a canvasser, one sees the full gamut of ways people can tell you to go away. The most common, and most misunderstood, is the “No Soliciting” sign. Be it a faded, peeling sticker on the door, or a plaque with an in-depth explanation of the many different disturbances caused by knocking at this particular door, “No Soliciting” signs are a common means for a household to try to avoid unwanted conversations with strangers. For many who put up such signs, these conversations include sales, religious proselytizing, fundraising, and political campaigning.

According to a number of court cases, however — most recently Citizens Action Coalition vs. the Town of Yorktown, Indiana, decided by a federal district court in 2014 — door-to-door canvassing is considered political speech and thus is protected by the First Amendment. Yorktown, a small and predominantly rural community in southern Indiana, passed an ordinance banning door-to-door solicitation before 9 a.m. and after either 9 p.m. or sunset, whichever comes first.

The ordinance specifically targets any “person who goes door-to-door for the purposes of disseminating religious, political, social or other ideological beliefs,” which “includes any person who canvasses or distributes pamphlets or other written material intended for non-commercial purposes.” The ordinance makes it clear that it means to include political campaigning and fundraising. But as the court decision against the town explained, sunset occurs in Yorktown before 8 p.m. more than six months of the year, and it occurs earlier than 5:30 p.m. for a number of days in December — considerably narrowing the window for traditional door-to-door campaigning.

The Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana (CAC), a group of advocacy organizations that relies on donations earned through door-to-door and phone canvassing, sued the town. Judge Richard Young, of U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, ruled summarily that ordinances such as this one infringe on individuals’ First Amendment rights.

Similar court decisions have been handed down since 1938, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in Lovell vs. the City of Griffin, Georgia, that requiring a permit to distribute “circulars, handbooks, advertising, or literature of any kind” violated freedom of the press, and freedom of speech and free exercise of religion as well. That case set an important precedent for broadly allowing canvassing and the distribution of flyers, declaring it a form of protected speech. Subsequent cases, including City of Watseka vs. Illinois Public Action Council and the 2014 Yorktown case, have further defined permissible time, place, and manner restrictions on soliciting. The Watseka case concluded that restrictions must be “content-neutral … leave open ample alternative channels for communication, and [be] narrowly tailored to serve [a] government objective,” such as residents’ safety. All the cases reinforce the bedrock notion that noncommercial canvassing, as a form of political speech, is protected by the First Amendment, and may not be abridged in the same way as door-to-door peddling.

So what does that mean for John’s “No Soliciting” sign in the Seattle suburbs? In short, it is irrelevant to noncommercial home visits, be they for the purpose of religion, government, or politics. For campaigns, this means we can do our jobs enthusiastically and thoroughly, contacting as many potential voters as possible and building support through face-to-face interaction, rather than constantly flooding the airwaves and mailboxes with advertisements. Some may regard it as a nuisance, and they certainly have a right not to answer the door or to slam it shut, but to me, canvassing seems like a human and worthy, even noble, way to sustain democracy.

Gustav Honl-Stuenkel is a member of the Class of 2020 studying philosophy and government in the College and is originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota. He has studied abroad at Sciences-Po in Lyon, France, where he examined French politics, especially regarding free speech norms.